Phenomenal phenomenological phenomena.

In the western world, the built environment is increasingly designed for sight alone.1 Despite the pleasing nature of spaces that engage multiple senses, many designers are cautious about building them out of a fear that the result will turn out too ‘Disney’ and therefore be taken less seriously. 2 The avoidance of sensory features is understandable – designing for the senses is difficult. Subtle or static sensations are not always noticeable, or can feel stifling and monotonous over time.34

Phenomenological spaces engage the senses and the mind. Perhaps despite their name, they are not inherently physically pleasant. They may instead serve to bring about wonderful realizations or understandings. That is to say, our title, ‘phenomenal sensation’ refers not only to our standard biological senses: sight, smell, sound, touch, and taste, but to our other senses as well – our sense of right and wrong, good and bad, our sense of intuition, of beauty, of fear, and other such things that are difficult to pin down but nevertheless clearly and obviously there – in the background, and sometimes the foreground, of our experiences of the world.

Knowing that you have the freedom to leave a place can suddenly render even wildly unpleasant sensory spaces downright enjoyable. Imagine relaxing into a dimly lit library after taking the subway there, or stepping in from a snow storm into a lodge with a roaring fire. Both scenarios are that much more pleasurable because of the presence of their opposite nearby. The challenge of enduring discomfort in the quest to find comfort, paradoxically, is part of the joy of it. 5

Of course, not everyone finds elation in the same ways. Culture, experiences, and many other factors come into play. Universally, sensation defines the way people move through the world – it is intertwined with emotion, mood, physical sensations, memory, how people think and act, and what they feel is possible. Most people hate the sound of a fly buzzing around their heads. Most people love the sound of leaves rustling as a gentle wind passes through the trees.

Finding a balance between comfort and challenge is an eternal quest – in physical environments, professional ones, and social ones, to name a few. Nobody likes feeling stuck or static. We enjoy the occasional challenge – so long as it’s not too difficult. There is joy in overcoming obstacles.

Balance is not a static state.

‘Eudaimonia’, is a Greek word that refers to the type of happiness that arises from living virtuously.6 This is a happiness that is tied to the ongoing practice of finding equilibrium between what is required by morality and what is required by self interest. Of course, 'living virtuously' isn't something that people talk about too often nowadays, but it is a useful paradigm through which to understand extremes without getting bogged down in explicitly physical characteristics. In his book, Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle talks about balance and sensation. He lays out an argument that puts virtues into the context of their related vices, where the excess of a virtue is a vice, and the deficiency of a virtue is another vice.

Consider courage, which sits between the two extremes of rashness, and cowardice. Rashness is thoughtless action without care for consequences. Cowardice is inaction characterized by fear. Courage involves recognizing that there is risk, and persisting through it anyway. Morals aside, most people get stuck somewhere out of balance on something. It can be hard to motivate a change in behavior, even if it’s for the best. Learning balance – morally, thermally, professionally, socially, etcetera – is difficult no matter what, but it’s easier if there are examples to follow.

This is even true – maybe especially true – for overcoming difficult imbalances. When someone has an extreme phobia, they heal through exposure to the source of their fear. Reductively, this is called ‘exposure therapy’, and it generally seems to work by demonstrating that there is a mismatch between perception and reality. It allows the person with the phobia to realize that they don’t need to be as afraid.

In Pesso Boyden System Psychomotor (PBSP) therapy, people are guided through scenarios where they act out traumatic memories and relationships with the aid of props. This process demonstrates how helpful it can be to physically engage mental challenges. By physically acting out traumatic memories, people are sometimes able to work through these memories and reframe them through more empowered personal narratives. The physical reenactment of a challenge – with a different outcome – provides a forum for practicing more resilient behaviors in the face of difficult encounters in the future, too.

Let me say that again. The physical reenactment of a challenge – with a different outcome – provides a forum for practicing more resilient behaviors in the face of difficult encounters in the future, too.

Both exposure therapy and PBSP involve real world physical objects and environments.7 They seek to address mental hang ups by mirroring internal conflicts in the physical world, and they help people see paths to re-balancing: the inner world with the outer world, the requirements of the self with the requirements of living with others, the need to trust and necessity to protect, the vulnerability of healing and the dance of flourishing. These therapies serve to open the door to sensations that are curtailed by physical and psychological limitations clogging our sensory receptivity. They are trauma plumbers that clear out perceived limitations by providing examples that demonstrate what is possible.

The relationship (made clear by these therapies) between an inner psychological world and an outer physical world, brings up an interesting series of questions. If a physical space were designed to mirror an internal conflict, could occupying it help someone see their own situation more clearly? The therapies described above suggest ‘yes’, but practically, would a space designed to challenge an inner conflict be effective for many, or are inner conflicts unique to the individual?

What about challenges like overcoming loss, recovering from heartbreak, or learning moderation? How could a physical space challenge the mind through its imbalances while simultaneously respecting the emotional sensations that arise? How might an ‘inner’ gym – one designed to train emotional intelligence – look? Let’s consider a few diagrammatic examples designed to explore this concept - to challenge the role of sensation in the physical world, and to demonstrate the potential of physical space to re-balance inner conflict.

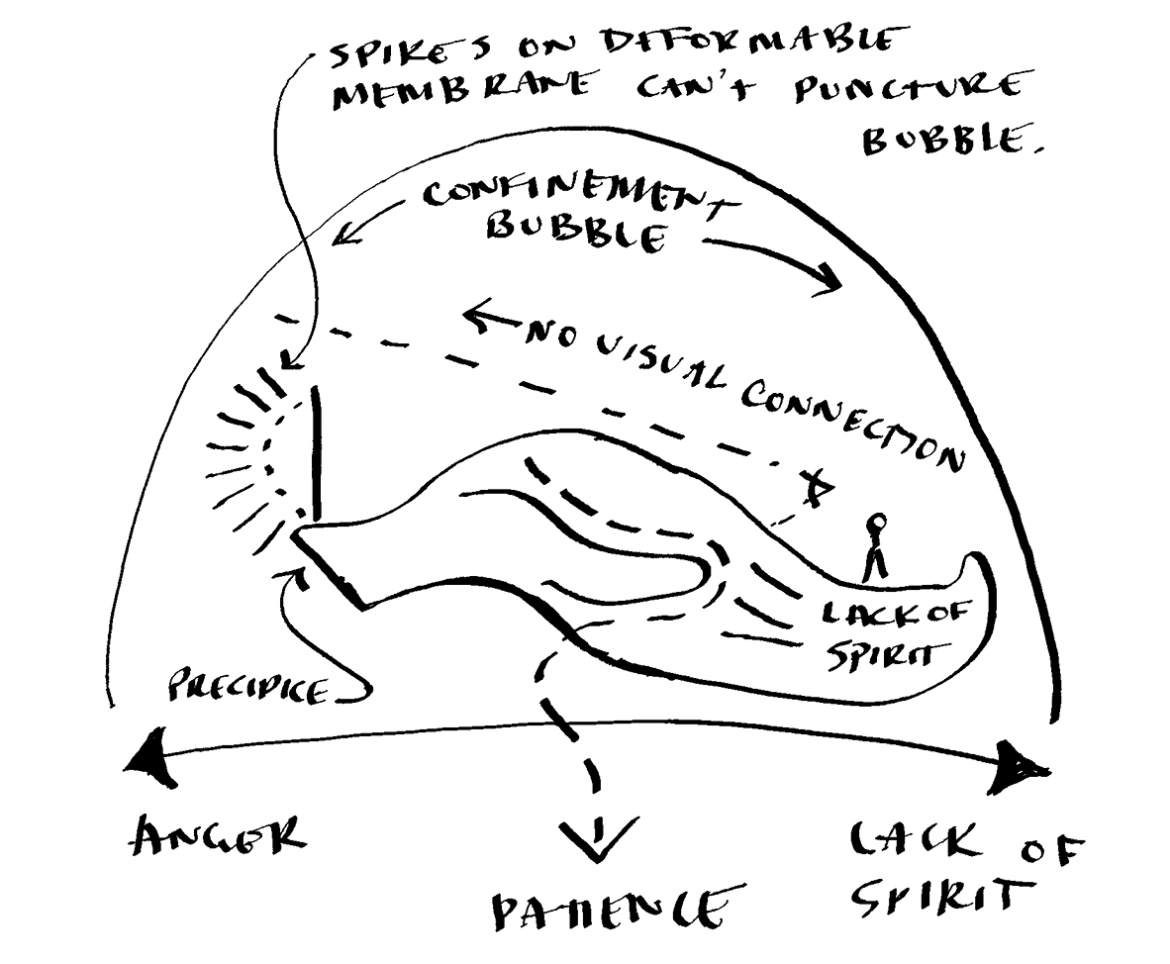

Patience Training: Anger and Lack of Spirit

Patience is the mean between anger and lack of spirit.

The resolution to an excess of anger is not to abandon the feeling, but to avoid becoming overwhelmed by it. Anger is a poisoned root with a honeyed tip that feels good in a moment but causes damage to the soul and psyche soon after.8 Indulging it is addictive – it feels powerful and invigorating. It is easy to recognize the lure of it – the feeling of righteousness that arises from this empowered expression of care.

Conversely, lack of spirit. Detachment is a form of safety – if you do not connect enough to care, connections can never be severed, and severing is painful. If you never connect, you free yourself from the potential pain of detachment later, you keep yourself safe and comfortable and free of suffering. Yet, living without care is not fully living, and the only resolution is to begin emotionally investing again.

So, at either end of Patience are alluring vices – despite their destructivity – it is easy to see how people might be drawn to a state of anger or lack of spirit.

In a physical space designed to lead someone towards patience, the beckoning pleasures of both should be represented. The space must have empathy with every position, or else the choice of moderation would be a false one.

Patience is not an emotional indulgence – it doesn’t actually feel very good at first, but through persistence, it begins to feel the best of the three options over time. Regardless, it’s a difficult sell. People may understand that patience is the way out of anger or indifference, but in practice, the discomfort of it is a deterrent.

Spatially, this means that a training room designed to find balance in patience will consist of three parts: one area that embodies deep care, power, and righteousness, (anger) another that embodies the freedom and protection of detachment, (lack of spirit) and a third that strikes a balance between the two (patience). This third space should probably also be less immediately appealing, and lead to the best outcome over time.

How does it look?

A large semi-translucent pneumatic structure surrounds a massive stone sculpture of a human hand. The fingers of this hand-like structure are cupped together, with the heel of the palm raised higher than the fingertips. At the wrist, the ‘skin’ of the hand is hot and rough. Wrapped tightly behind the heel of the palm is a disc-like bracelet.

It sits such that the side of the disc facing the hand is a smooth deformable membrane, and the side facing out towards the wall of the pneumatic structure is covered by a field of spikes attached to the membrane. It smells faintly of burning rubber and metal. At the other end of the wrist is the cupped palm of the hand, large enough to sit inside comfortably, nestled between the cupped fingers. The skin in the palm of the hand is smooth and cold. You sit in the palm and breathe in deeply through your nose, but smell nothing. From both the bracelet side of the hand and the cupped palm, the surface of the bubble is out of reach. You must escape the bubble.

Where do you start? You may first be drawn to push the deformable membrane of the bracelet. If you do, it shoots spikes towards the inflatable structure. The spikes respond immediately to the pressure, but they don’t reach far enough to puncture the bubble. Promising. Perhaps if you push the membrane far enough, you can move the spikes close enough to the structure that they will pop it. You back up and sprint towards the membrane – pushing with all of your might. The spikes move with every tiny movement of your body, yet, your efforts are in vain. The spikes fall short.

Discouraged by your failure, you may wander to the palm. Slouching in defeat, with your back against the hand, and your feet dangling between the fingers, you feel comfortable enough, and calm.Yet, lurking in the back of your mind is the understanding that while you sit here, you make no progress towards your freedom. It might provide a relief from the energy and intensity of thrashing at the spiked bracelet, but the relief is soon replaced by restlessness, listlessness, or futility.

You tried the bracelet, you sat in the palm, neither of which advanced you towards your goal of escaping the bubble. What next?

While you are walking back and forth on the hand, confused about how to move forward, you notice a gap between the thumb of the hand and the palm. Without any other options, and with a slight sense of dread (you could get stuck in there) you decide to risk passage through the gap, in order to see if there are more promising avenues for escape once you are off the hand.

The squeeze is tight and wriggling through the small space is wildly uncomfortable, confining, and claustrophobic. You feel stuck and weak, but as you persist, you make it through the hole, and there below the hand, is your exit.

Training Liberality: Extravagance and Stinginess

Freedom to give and spend time, money, or other resources without prejudice is called liberality. Extravagance represents an excess of liberality, and stinginess represents its deficiency. As with anger and lack of spirit, both extravagance and stinginess are alluring in their own right.

Lavishness is the stuff of fantasy – It can feel really good to imagine, but it is very difficult for most people to achieve extravagance in a sustainable way. In reality, living extravagantly – above your means- can mask the reality of needs that are not met. By this I mean, when you don’t have enough money to put gas in your car, suddenly the Prada sunglasses you bought might feel less exhilarating.

Now that we’ve established the danger and appeal of extravagance, I’d like you to imagine a scenario with me. Let’s say you acquire some money, and you suddenly feel secure. Excited, you share the news with some friends. Once you do, naturally, they ask you to share the wealth. You want to meet their requests, but after counting out what you have, you realize that if you do, your treasure will quickly become no treasure at all. You hem and haw over what to do, and ultimately decide that you won’t share it, and instead, keep it for yourself.

Making this decision, you feel protected from winding up broke again. This feels really good. Yet, when you tell your friends what you’ve decided, the looks on their faces cause you to doubt yourself again. Your cheeks fill with shame, but you remind yourself that you will be poor again if you share too much, and so you stick to your initial decision. Over time, your wealth grows and grows, but your connections with others become distant, then strained, then one morning you wake up and realize that you don’t feel close to anyone anymore.

The joy of extravagance is in the feeling of endless potential and the freedom of having – or being – anything you want without worrying about the consequences. The joy of stinginess is in knowing that you have control over your things. The cost of both is security – your personal and financial security, or the security of strong social connection – both of which need reinforcement in order to flourish.

How does it look?

Imagine that you are inside a giant cedar beehive. The smell of clean dry wood, the characteristic hexagonal portals line the space from top to bottom. At the center of the hive is a platform on a spring. When you step onto it, you bob up and down like a jack in the box. You hear an engine kick on, and suddenly, little plastic balls filled with dollar bills begin to patter in from the ceiling like snow. From the platform, you can reach out to grab balls as they fall, or watch them flutter down around you. When you catch one, it feels like you’ve caught the golden snitch.

At the bottom of the room, there is a hole. After the balls fall past your platform, they drain through this hole. The hole is big enough to be covered by your body if you lay over it, but in doing so, the weight of these balls bears down on you over time, squishing you, and if you move, they pour out through the hole.

You stand up, and watch the balls fall through the hole. Walking around the space, you notice that tucked into the walls of the hive-like room are hundreds of empty boxes. Suddenly, a clock begins counting down, with the number ‘3’ displayed below the timer. You drop a ball into one of these empty boxes, and the number drops. Now it reads ‘2’. You quickly fill the box with two more balls, and the timer stops. A few minutes later, another timer appears. Now the number reads ‘5’. You fill another box. Once the box is filled, the rate of balls falling in from above increases.

As you continue to fill boxes, new timed opportunities arise, and in exchange for filling the boxes, sometimes you are rewarded with a faster rate of balls, and other times you receive items that help you collect more balls. Sometimes the balls are just taken away.

One thing is for certain – stashing balls doesn’t hold a candle to the simple pleasure of bobbing on the platform and watching the snow. It’s not possible to stash anything while you are laying over the hole at the bottom of the hive – a human drain plug, weighed down by hundreds of bills.

Training Modesty: Shame and Shamelessness

Modesty is the balance point between shame and shamelessness. Shamelessness is a lack of decency and consideration. Shame is a feeling of humiliation and embarrassment. Where acting without regard for decency, social rules, or the comfort of others may be shameless, shame is feeling foolish about what you have done.

Between the two extremes, modesty is a state of moderation. It has a strong relationship to culture, disposition, and religion because ‘decency’ and ‘propriety’ do. Because modesty is dependent on context, a singular training room for it would likely be more successful in some cultures than in others.

Regardless of the factors that cause it, for most people, shame feels like hot cheeks, a pit in the stomach, tension in the shoulders, and coldness in the legs. Shamelessness is an exhilarating rejection of the invisible tethers that connect us to the people around us. Unlike liberality and patience, shame is not a desirable state – there is no inherent appeal to it. It feels downright bad.

There is no way to avoid conditions that might lead to shame. You can land there by accident by not understanding yourself or the – often unspoken – rules of conduct governing your environment.

As a result, modesty must be trained in the presence of others.9 Perhaps the best form of training that currently exists for it is stand up comedy. Anyone who has seen standup may doubt that it has anything at all to do with modesty, but modesty is about finding the balance between your tendencies and what is expected of you. If no one is laughing, you haven’t found it.

If you keep practicing, eventually you get closer. You learn more about your environment and yourself by continuing to put yourself out there, and by paying attention to the reactions in yourself and your audience.

The physical experience of this type of space changes drastically based on the people within it. The feedback of performance and reception defines the physical space.

A stage is something like a play environment – it may be you who is standing up there, but it’s also not real life. There is a line between ‘you’ and ‘stage you’. This is enough of a difference for most people to feel that they can say different things on stage than they would in other circumstances.

The feeling of tens, hundreds, or thousands of eyes on you, the sound of clinking glasses, your heartbeat behind your eyeballs – and hopefully laughter from the crowd – the feeling of the bright light in your eyes, the reverberations of your projected voice through the microphone in your hand and the cavity in your chest – the cadence and rhythm of the performance and it’s reception – a comic, in this setting, creates an architecture of sensation without any physical materials at all.

Now if you still don’t buy that stand up comedy trains modesty, hear me out. One person’s modesty might make another person raise their eyebrows, but this is completely not the point. The point is finding a balance that aligns with the true nature of you as an individual, and the inner leanings of your heart.

If you do this authentically, the way that good comedy does, the frequency at which you land feels good to others too – even others who disagree with what you are saying – it lets them tap into the real within themselves, it lets them think and feel their true authentic feelings. In this way, comedy is an instrument of authenticity and an agent of modesty in culture.

The immediate feedback of the spoken word in this dynamic setting creates a space that is as real as any four walled space with a door. Is it possible to fail in this arena? Absolutely – and even the professionals do so all of the time. That’s part of the challenge, and therefore also part of the joy when you succeed.

Summary

In all of these rooms, you are asked to move through physical space while doing mental work. In games, in love, in real life, and in any worthwhile pursuit that I am aware of, changing your position along any spectrum involves feeling both powerful and helpless. Learning more about yourself and your values and changing your behavior so that it aligns with your inner compass doesn’t always feel good right away, but if you persist and get there, it feels unbelievably, well, phenomenal – indeed much much better than accepting your position anywhere else.

One of my good friends said to me once, ‘I’ve decided to be myself because being anyone else is just too damn hard.” True, it takes work, but it’s worth it. Phenomenal sensation training rooms are kind of like seesaws – they balance indulgences and ascetics, self interest and generosity, discipline and reward.

They are play environments where you can test out how you truly feel, what your priorities are, and what feels most right for you. Of course, they push you towards finding moderation between extremes, but finding the tipping point is completely an individual pursuit. There is a way to win or succeed in every room, but that way can be very dependent on the occupant.

The examples in this post are examples of spaces that could serve as practice rooms for finding inner balance. Until they are built, it’s hard to know how they will function. Maybe some are more effective as theoretical explorations than physical spaces, and maybe some of them help people to overcome challenges they have been facing for a lifetime. Time will tell.

These interactive machines, architectural installations, and physical metaphors are designed to test how virtue, resilience, balance, and mental fortitude can be trained by actively engaging with the physical world. They are based on precedents of therapies and artworks that instigate emotional and cognitive responses similar to the ones that are investigated here. They present moral dilemmas as fairytales do: The hero undertakes an epic adventure – they make choices and mistakes, they experience hardships, and in the end, they find their way.