Design for the Human Experience. For decades, we’ve understood that architectural design has a profound impact on human psychology. The recuperative effect of biophilic views,1 the academic boost from natural light in classrooms,2 and the inspiration derived from high ceilings3 are few of many widely cited examples that demonstrate the impact of atmosphere on wellbeing. Yet, as our awareness grows, so too does our responsibility to integrate these insights into more nuanced designs that benefit people holistically.

In recent years, research in environmental psychology has surged, indicating a widespread collective desire for spaces that enhance well-being. This surge is not simply an academic curiosity but one that has pervaded popular culture and has become central to the discussion about the future of our planet. There has been a call to action for designers and architects to create spaces that are healthy, that positively impact the earth, and that feel good to occupy.

Some exciting recent studies describe the impact of green spaces4 and indoor plants5 on mental health, productivity, and wellbeing, even virtually. 6 They identify environmental factors that influence the cognitive functioning of older adults,7 and mental health more generally,8 and they definitively show that the design of spaces can influence behavior, satisfaction, and stress. 9

A Longstanding Psychological Epidemic. In 2014, Dr. Bessel Van Der Kolk, a renowned psychiatrist and trauma expert, revolutionized our understanding of trauma in his New York Times #1 bestselling novel, “The Body Keeps the Score.” His work emphasizes trauma’s physical manifestation, steering the mental health field towards treatments that incorporate bodily experiences. Techniques like EMDR and Somatic Experiencing have become more widespread from this perspective, emphasizing the essential role of physical engagement in processing and healing trauma.

This has led to a newfound widespread sensitivity to the topic, and interest in the phenomena of healing and growth. There has been an explosion of efforts in recent years that aim to help people heal, and to raise awareness about the impact of psychological injury.

This includes neurobiological research, in which the use of advanced neuroimaging techniques has provided deeper insights into how trauma affects different brain regions, such as alterations in the amygdala and hippocampus, which are crucial for processing emotions and memories. 10

Other developments include Dr. Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory,11 advancements in epigenetic research on the intergenerational impacts of trauma,12 and the increased use of Virtual Reality in Exposure Therapy13. In recent years, there has been a marked increase in the adoption of body-centered14 and integrative approaches that combine psychological, physical, and sometimes spiritual methods to treat PTSD and promote healing.15

Trauma-Informed Design. In response, architects and designers have worked to develop ‘trauma informed’ environments.16 These spaces aim to promote feelings of safety and security. They do so through temperature control and privacy, clear signage for way-finding, visibility and navigation.17

They include access to natural elements such as windows with views of green spaces, indoor plants, and natural light18 – all features that have been shown to have a calming effect and to reduce stress. They reduce the risk of sensory overload by playing relaxing sounds, and using colors, textures, and materials that soothe rather than stimulate.19

They are culturally sensitive and flexible – so they can be reconfigured and adapted to allow individuals to use them in ways that feel comfortable and support their needs – such as the need to gather in community support spaces and build community.20

They are also mindful of trauma triggers – avoiding design elements that might trigger stress or traumatic memories.21 They are supportive, soothing, relaxing and comforting environments that seem like they could be useful in aiding recovery from acute trauma.

While the intentions are noble, this approach may not be going far enough. After the initial and crucial phase of healing that involves finding safety, people need more than soothing and calming spaces in order to recover. While these spaces seem like great places of refuge to find peace and build strength, they lack features common to many therapeutic methods that promote long-term psychological resilience.

The journey of personal growth encompasses a broad spectrum, where healing from past wounds sits at one end, and the pursuit of self-development at the other. This continuum reveals a profound truth: the strategies and insights gleaned from overcoming adversity, such as trauma, hold universal value, guiding us towards deeper self-awareness and resilience.

While trauma may represent an extreme on this spectrum, the process of healing —characterized by introspection, rediscovery, and adaptation— provides a blueprint for personal evolution that is applicable to all. In navigating through challenges, we not only mend but also discover untapped strengths and perspectives.

This transformative process, therefore, is not exclusive to recovery but is integral to any quest for growth. It teaches us about the resilience of the human spirit and our capacity for renewal, offering lessons in emotional intelligence, fortitude, and the art of thriving amidst life’s complexities. Embracing this holistic view, we see that growth is not merely about progressing from a point of struggle; it’s about harnessing our experiences as catalysts for a richer, more fulfilled existence.

We see that by learning from therapeutic practices, we can potentially glean insights into practices that, more generally, can be employed to help us grow and overcome challenges – whether they are related to injury or only to personal development.

Spaces designed for standard daily use should be easy to navigate, non-threatening, comfortable, and supportive of the activities that happen within them. However, those that proclaim themselves to be ‘healing’ should be more specific about how and what they are helping, and where they lie on the spectrum between healing and growth.

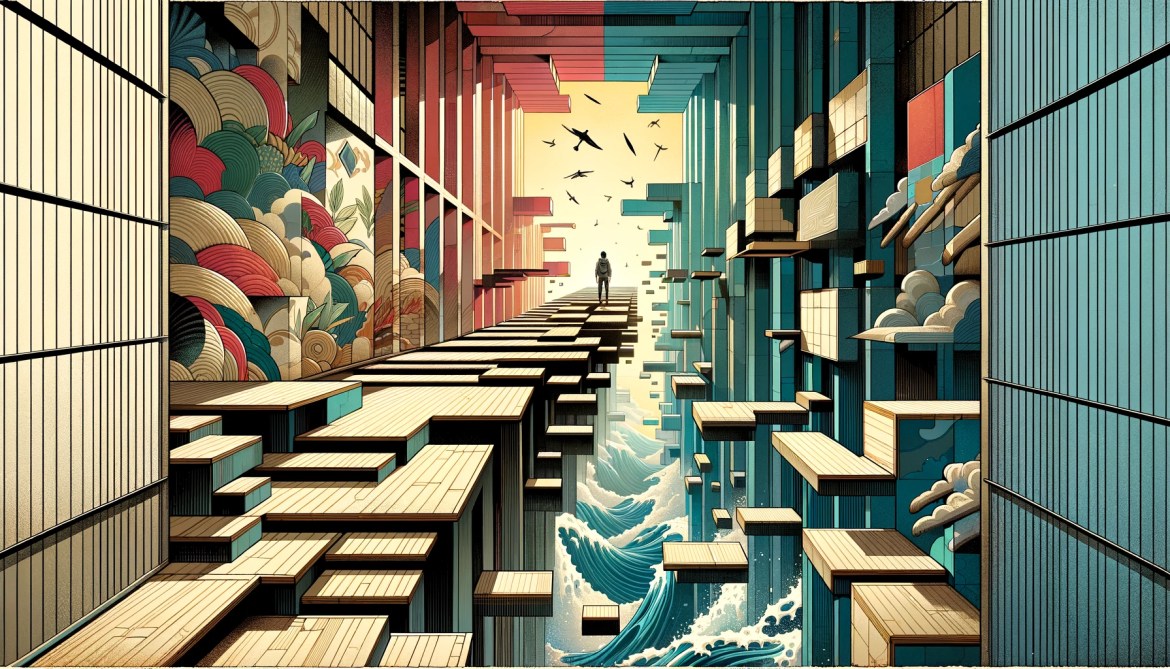

The question arises – can architecture, which is inherently somatic and psychological, do more to promote healing and growth than what has been proposed previously, and if so, how would this look? How would this type of architecture behave?

The Need for Challenge in Architecture. Unless the injury is acute, environments that coddle and soothe may inadvertently hinder one’s ability to confront and process trauma. Or, at the very least, they may not do much to help. Growth happens when you identify challenges, confront truths, process memories, and overcome weaknesses head on – despite fear. It is an active process.

Resilience is built by navigating that fear. Environments that mirror the complexities of life and its hardships, while training people to engage with difficult subjects and to believe in their ability to overcome them, may be more useful for healing, and facilitating lasting growth beyond this initial phase. I have seen evidence of this in my own experience.

After months of isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, I took a leap of faith and moved to New York City. This decision came after a prolonged period of stagnation and depression, where leaving my house had become a rarity. The contrast was stark: from the confines of my quiet Somerville, Massachusetts apartment to the bustling streets of a city known for its relentless pace and daunting challenges.

Navigating New York’s complex landscape was initially overwhelming. The city felt, at times, harsh and inhospitable, a far cry from the safety and predictability of my previous home. But this challenge became a catalyst for unexpected growth. Each day, as I explored the city, faced its trials, and interacted with its diverse inhabitants, I found myself shedding layers of fear and apprehension. I felt myself growing.

The process wasn’t easy. There were days filled with anxiety and doubt. Yet, with time, I began to feel a sense of blossoming. The city, with all its hardships and demands, was teaching me resilience. It was in facing these difficulties, not in avoiding them, not in seeking comfort outside of them, that I found a new strength and vitality within myself.

This experience reinforced a powerful lesson: sometimes, it’s the environments that test us, that push us beyond our comfort zones, that foster the most significant growth. New York City, in all its complexity, didn’t just host my journey; it actively shaped it, turning a period of depression and inactivity into one of thriving.

Beyond Comfort: Design for Resilience. Our bodies hold tension that accumulates over time in response to what we have witnessed, and what we have done – or not done. Muscles remember even when our minds strive to forget, but this built-up tension can be relieved. Therapeutic methods such as moving the body in creatively expressive ways, dancing, practicing yoga, participating in theatrical performances, and connecting with other people, are some of the many challenging practices that seem to work.

So, how can Architecture do more to facilitate growth?

This question forms the core of my research. In pursuit of an answer, I’ll provide examples from other fields that have made headway on the challenging problem of healing and growth – whether or not it was their explicit intention. In a series of posts, I will match insights learned from play, art, and architectural installations with their therapeutic touch points in order to identify and explore opportunities to push their success further in architecture.

Then, using these examples as precedent, I will endeavor to show how Architecture is well situated to do much more for healing than simply soothe and comfort us. The final proposition of this series centers around developing a type of space that serves a singular purpose: to train resilience. It is proposed to initiate a conversation around a more present and engaging form of architecture. These ‘resilience training rooms’ are concepts for spaces crafted to strengthen mental fortitude, where the architecture itself challenges and supports individuals in equal measure.

This exploration is a compendium of resources and thoughts that I believe may be useful for identifying opportunities. It is not a treatise, nor a recommendation for best practices. It’s an invitation to continue to envision architecture as an active participant in our psychological and physical health, and to consider more ways in which it can continue to serve us. The aim is to imagine the role of architecture as an active force, designed not to soothe but to empower, not to shelter but to prepare. Let’s harness the transformative power of design to create spaces that do more than comfort— spaces that teach us, challenge us, and help us to heal.